Is it possible to talk meaningfully about longform media on shortform mediums, or are Twitter conversations about Infinite Jest invariably doomed to failure? In today’s fast-moving and increasingly algorithmic social media landscape, the weight of our discussions often cannot be borne by the fragility of the platforms we’re forced to use for them. Shortcuts into our deeper meanings are inevitably invented.

When trying to articulate the beauty of a movie you’ve recently watched, having neither the inclination nor tools to write an essay, one might simply reblog a couple gifsets to their Tumblr and write “GOD. And I need to lie down,” in the tags. It’s understood that gifs are not representative of an entire film, but it’s also understood that by choosing which gifs to tag #She Should Kill Me! underneath, you’re making a value statement about what was, in your opinion, ‘the good part’ of the movie (or at least where its primacy of meaning dwells). Multiple compilations further coalesce into one tapestry of opinion, social media’s brevity subverted through summary.

You can lift heavy topics with a weak shovel in this way. You’ve pointed to particular places within the film that had personal meaning and successfully cobbled together—well, if not a peer reviewed thesis about the movie, at least several utterances which represent your opinion fine enough. It’s fractious but functional.

And then there is another increasingly common way to achieve this tapestry effect.

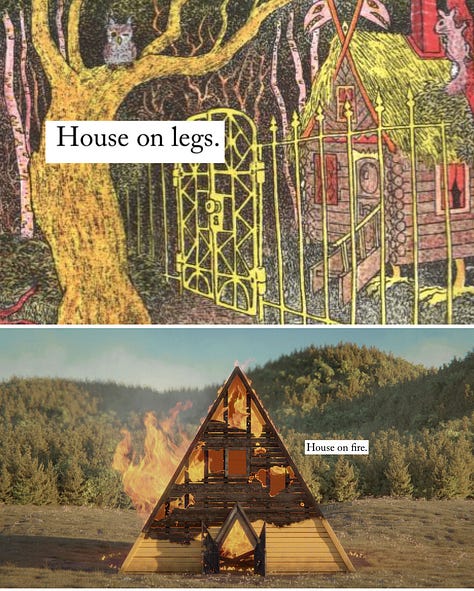

This type of post, sometimes called “web weaving,” compiles scattershot fistfuls of excerpts from different pieces of art (no distinction made for medium) with similar themes and imagery. A web weave is a singular tool for mashing five or six different artworks together and making their interpersonal relevance immediately obvious.

Placing them together is a statement about their thematic unity and intellectual connections. That placing together, the induced proximity of these artworks, is meant to compensate for the limited frame of each tiny piece. If movies are represented by a gifset, a novel might get a paragraph—yet these two tiny windows together theoretically conjures a powerfully emotional understanding of whichever uniting concept they share, achieving resonance in a way that they’re unable to individually.

Web weaving also serves to make identity statements, helpfully chaining literary concepts/thematic focuses/character archetypes and their representational manifestations together quickly, bluntly. You’re the kind of person who liked Interview with the Vampire (2022)’s feminine ennui? Here’s some other stuff with the same vibe and a fast track to ‘the fundamental essence’ of that stuff.

This genre of post is unique to social media’s way of talking about art. Even the label ‘web weaving’ has an internet-specific modernism, suggesting that one is connecting the dots1 by spinning an intertextual spiderweb, or crafting an interweb-friendly aesthetically minded scrapbook of snapshots. Relevance is a ghostly suggestion. Meaning is made through reference. Deliberately placing summative screenshots side-by-side serves as a way of fighting against the sheer volume of art that anybody has access to at any second. There’s so much to watch and read and view and comprehend and absorb, but here’s something you already like and a shortcut to its deepest emotion. You can look up what you don’t recognise. But you don’t have to! Everything important is summarised nicely here for you already.

Most immediately suspect about this form of artistic engagement is the shallowness of it. The overgeneralization it encourages is impossible to ignore.

While curated representations may tell you different, one of the main wonders of artwork is their tremendously particular, individual, and incomparable specificity. Deborah Landau’s 2023 collection Skeletons2 is composed of eight line acrostic poems all called SKELETON—all the same length, all the same base word, all the same topic (guess), without once reducing either Landau’s subject matter or approach into sameness or repetition. The collection as a whole is more than the sum of its parts, but this is only possible because of the specialness and uniqueness of those parts.3 Skeletons achieves a precise articulation of a particular feeling that a web weave organised around the idea of ‘skeleton’ could never accomplish. Only Deborah Landau could have wrote Skeletons, and only Deborah Landau did.

Presenting dismembered limbs from nine different pieces of art, and not even disclosing where they came from, feels like grave robbing. This is not literary analysis. This is Frankenstein.

The subtext of this approach is that it’s impossible to truly know any of the artpieces composing the woven whole, and that you need these outtakes because the entire individual works are too big to hold in your head. When left to perpetuate unexamined, this habit is degenerative. Engaging with art like this diminishes our capacity of artistic appraisal and our media literacies.

We must empower our memories. We must trust ourselves to be able to know.

Skeletons’ power draws from the observation and recall of Landau’s readers. She respects and trusts her audience’s ability to notice certain charges imbued in certain words, and builds a collaborative language by trusting the human memory to remember subtleties from earlier on. She, and everyone who’s ever written a novel, is right! Honouring memory and investing in memory is the remedy to social media’s conversational splintering.

Citations online are often dicey, on not just web weaving posts but any short excerpt of a longform project you may find on social media. An artwork is relevant enough to the central picture you’re trying to capture that it’s worth inclusion in the web weave so you can trade off its gravitas, but yet the full text is not seen as important enough to properly credit or make available to readers.

Art presented in this way is a fragmented experience. There isn’t an explanation of why the different pieces are placed together, as connection is meant to be inferred rather than explicitly stated. The organisation of juxtaposition, the kaleidoscopically broken thematic links between them—all this encourages readers to ‘stop here’ after learning about new art in this manner, rather than to ingest and invest in them utterly.

When was the last time you devoured a book? Read it three times. Highlighted/underscored/dog-eared. Memorised your favourite passages and thought for hours about them, retraced pages and compounded upon the thoughts you had on each tour, obsessed about turns of phrase, lightness of movement, trajectory of character. Absorbed every scrap of meaning and let it linger in the stomach? This is memory that becomes reverence. Near physical, kinetic and vivid and specific. Let it make a house inside you.

Neil Postman4 was concerned that the medium of television would flatten the importance of all information it presented down into the same level of significance. His book Amusing Ourselves To Death contended that news stories running directly beside toothpaste commercials beside Flintstones reruns would confuse viewers into thinking all three are the same kind of video. Postman worried the volume of content humanity has access to would become so overwhelming that the only way to stand out amongst the crowd would be to appeal to our sense of entertainment, and therefore ‘sober and serious’ longform stories would die out in favour of whatever advertisement or trashy show edited the most sparkles onto itself in order to appeal to the lowest common denominator, in a sort of post-intellectual glitter explosion.

On the surface level, a social media news feed might resemble Postman’s tinfoil-hattiest prophetic nightmares. But isn’t web weaving actually a remedy to his significance problem? Isn’t a human person linking similar points of interest together a straightforwardly positive expression of Art Enjoyers looking out for each other?

Postman would tell you it would be, if only! social media itself wasn’t acting as an executant, interrupting the natural pathway between seeing a recommendation and experiencing the full work, imposing itself and its limitations into the halfway point of that transaction.

Every medium of communication, I am claiming, has resonance, for resonance is metaphor writ large. Whatever the original and limited context of its use may have been, a medium has the power to fly far beyond that context into new and unexpected ones. Because of the way it directs us to organize our minds and integrate our experience of the world, it imposes itself on our consciousness and social institutions in myriad forms. It sometimes has the power to become implicated in our concepts of piety, or goodness, or beauty. And it is always implicated in the ways we define and regulate our ideas of truth.5

You may have heard this one: the medium is the message. The philosophy of the medium is quantity over Quality.

The comorbid complication here is a problem of attention.

Rather than longform media disappearing, our individual ability to longterm focus on any one particular thing could be waning into the internet event horizon.

Disconnection from the art that you love is not unique to Tumblr users that like to index their tags. This is emblematic of the passivity modern day internet users are encouraged to maintain. Companies want you floating along the surface of whatever content stream they’re making money feeding you, because that’s how supply demand and quarterly revenues work. Fearmongering headlines that “PHONES are DESTROYING your CHILDREN’S ATTENTION SPANS!” completely fail to understand the actual consumption dynamic, which is people doing their best to apply focus into as many important areas as possible and media empires who make their bank off retention rates doing their best to persuade everyone that Their Thing is the most Important Thing in the Whole World.

Neither Postman nor phone-melting-brain article writers nor the cyclical nature of the content mines trust human dedication, the human mind. Prove them wrong. Trust yours.

As Haweya’s article On tailoring your social media experience warns us, if your understanding of an idea (in this case artwork) is conducted exclusively in a limited medium, the medium’s limitations will block pathways of thought which it finds difficult to support. Here lies examination and nuance; RIP.

Most of us are familiar with the Mcluhanian idea that the medium is the message. We know that these platforms have an effect on what we say, how we say it, and how it is received. Though we still seem to be acting like this isn’t the case. We act as if we agree with several techno-capitalist notions, such as their platforms being value-neutral and having no bearing on what is being said; That the onus is on us to use these platforms responsibly— and that the use of these platforms is completely unavoidable.

Invisible compromises are being made. Nuance is traded for visibility. All of our solutions to social media involve using it correctly instead of using it less.

Even while debating the virtues and vices of social media, we quietly conform to its logic. Adopted at their highest level, these platforms strangle our imaginations and make us believe that the only versions of our values and politics are these mutilated versions found online.6

It’s threatening to optimized corporate profits when people develop real relationships with art. When read properly, adoringly, deeply, one poem lasts a lifetime. You can stop buying.

Love for one writer will naturally lead you down a beautiful path to their inspirations, colleagues, references, and peers. Your enchantment with a single painter or sculptor or fashion designer will organically spread to their surrounding art movements and rivals and mentors and apprentices. Then artificial injections of New Media Suggestions, From Vox, will bounce off the bulletproof glass of your genuine fascinations. You will know what you like and you will remember the exactness of its beauty. The tighter your focus the wider your world, and richer. You’ve got to be less normal.

Texture loss is another problem with the philosophy web weaving represents.

When everything lives online on the same feed, excerpts from art are contextualised in relation to other excerpts from other things and not from the full body of work they were pulled from. The possibility of evaluating an artpiece’s independent features against its whole is replaced with the dubious benefit of comparing an artpiece’s most quotable line against slices from six other artpieces that happen to share keywords.

Everything takes on the same flatness and dimension. Texture and tangibility vanish.

Not just in web weaving posts, but on aesthetically crafted Letterboxd lists and self-conscious Reddit forums, Instagram feeds everywhere, and more Twitter threads than God could count, the siren song of isolated vignettes. This is little more than a status update, mood music, shallow gesturing at cultural literacy motivated by glitter edits, curated for visuals, symmetry, badass quotes. Not to me. Not if it’s you.7 We are lured into maintaining a coherent aesthetic of artwork that looks good together and makes us look cool in front of our friends, suggests we’re cultured and intellectual and with it but quirky—and has made no impact on our psyches whatsoever.

Is this a disingenuous take about people having fun with .jpegs online? Certaintly the bulk of this engagement’s usebase wield harmless motives, paper swords. But it’s self evident that focused understanding is better than vague recognition. And you can’t lose yourself in a delicious meal if you keep glancing at other people at the table, hoping you haven’t got ketchup on your face. But I promise love tastes better when the only opinion you centre is your own, and you allow yourself to chew right into the heartmeat of your feast. Unhinge your jaw.

It’s entirely human to notice linkages between things that you like and to get excited about pointing them out. This is made all the more exciting the more disparate your starting places are, because connections are assumed to mean more if you have to work for them.

Contextomy is a dishonest argumentation technique where you quote people out of context in order to destroy them in the free marketplace of ideas. An example of contextomy would be cutting a politicians thirty minute speech about the complicated ethics of Alberta’s oil sands and the future of Canadian power down into the single sound bite: “Alberta’s energy industry is doomed.” Perhaps the politician technically said this, but that comment is not representative of the sentiment of the whole speech,8 and it’s not conductive to productive political (or ethical!) discourse to pretend that it does.

This is the monster web weaving enthusiastically feeds. Celebrating snappy little bytes cleaved from a nuanced piece because the false representation is more understandable and immediately palatable than the entire picture.

Humans naturally value continuity. Sometimes you have to be a little creative to draw a coherent line from A to B, and we’re willing to do it because the idea of the line appears virtuous. Yet it’s a fallacy that something has to mesh perfectly into the preexisting fabric of your life in order to hold value. The glamour of coherence is a false one. The satisfaction of continuity has nothing on the delight of discovery.

The connections between your interests and emotions can also be called Your Personality. Understanding your fascinations is understanding yourself. Yet language is difficult, the medium is public, nobody can read all the books in the world, and it’s tempting to wave a supplicating palm in the direction of art that matters to you and leave it at a, “like that, I like those ones.” But it’s inherently valuable to introspect until you understand why you love something and what particular aspect is enthralling you. Ruthless self examination is scary, and it’s unavoidable in any meaningfully close reading of a text. Yet this process strengthens your tether to everything wonderful, everything valuable.

As David Foster Wallace puts it, “the liberal arts cliché about teaching you how to think is actually shorthand for a much deeper, more serious idea: learning how to think really means learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think. It means being conscious and aware enough to choose what you pay attention to and to choose how you construct meaning from experience.”9

Carefully crafted digital archives do serve meaningfully as a receptacle for thought, but we must be vigilant to not outsource all our memories to them. The “I can just look it up later” mindset quite literally removes the human ability of retention. Unstretched muscles atrophy. If memory fails then the mind is air in a skull.10

A critical prerequisite to intellectual ownership is memory. You must be able to fix and hold something in your head before you can rotate it like a rotisserie chicken.

Knowing a poem by heart or being able to exactly quote a speech you heard has a connotation of intellectual snobbery that it doesn’t deserve. Nina Kang professes the value of memorization while still acknowledging its difficulty in her piece The Lost Art of Memorizing Poetry.

These days, memorization, like corporal punishment, is something our culture has largely evolved beyond. We might all know the first verse of Jane Taylor’s “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” but beyond that it’s hit and miss. In the age of search engines, perfect recall is no longer prized—just remember a couple key search terms and we’re good to go. Learning to remember has been replaced by learning to skim, and when yesterday’s viral video or trending tweet scrolls below the fold, it leaves barely any imprint on our collective consciousness.11

However, there is an optimism Kang doesn’t see—the art of knowing art isn’t lost. It’s possible and critical, insufficiently satiated by web weaves and Twitter weaves, still there, persisting valiantly.

Many cases could be made for the idea of investing fully in a single text, and much intellectual ink has been spilled over determining to what extent you ‘should’ learn, but it truly is simple.

Which words do you want to have with you forever?

Perhaps the most extreme possible example of somebody knowing the exact answer to this is Tatiana Gnedich, who set the bar low for everyone by memorizing seventeen thousand lines of Don Juan and translating it, in her head, into Russian, while simultaneously serving ten years in a Soviet labour camp.12 The human spirit endures.

What will be with you when you’re completely without objects?

Discern, decide; let love lead you.

Compilations are not actually the posts of Satan; some of them are cute. The trick is to pick actually shortform subjects, such as ‘meta’ web weaves of other social media posts. The critical distinction here stems from the shortness of the posts’ lengths—you can, actually, see the whole thing. There’s no need to ‘falsely represent’ because it’s just normal representing, no need to ‘cut down’ anything too big for the post.

With the whole flayed out under your eyes, you are the one empowered to decide what’s important.

Web weaving and the traps below its surface are indeed insidious, but conceptually it’s quite sweet to point at interrelated artwork and marvel at their unity of feeling. That’s human. That’s building a community out of beautiful shapes. And if you maintain vigilance against the call to inertia that aesthetic curation represents, social media can be a good starting place for your intense and specific relationship with art. You’ve got to find out about new things somewhere, somehow. But once you’ve done that—get offline, get yourself a highlighter or a DVD box set with directors commentary or a physical painting to hang in your office or a secondhand comic book with jam stains on it, and start digging your tunnel. Dig dig dig, into the centre of the earth.

Internalise in the viscera of your spirit: a text.13

Which Lara Glenum wrote about gorgeously for Poetry Magazine here: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/160308/the-ultimate-bone and which you can buy here: https://www.deborahlandau.com/skeletons

So whatever’s the opposite of a Buddhist that’s what I am. Kindhearted, yes, but knee deep in existential gloom, except when the fog smokes the bridge like this— like, instead of being afraid we might juice ourselves up, eh, like, might get kissed again? Dwelling in bones I go straight through life, a sublime abundance—cherries, dog’s breath, the sun, then (ouch) & all of us snuffed out. Dear one, what is waiting for us tonight, nostalgia? the homes of childhood? oblivion? How we hate to go—

This excerpt available from “The New Yorker,” accompanied by an audio reading of the poem by Landau here: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/05/17/skeletons

Find a summary of Postman’s philosophy and career, and links to his publicly available articles, at this fan page: https://neilpostman.org/

Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, 20th edition with new introduction by Anthony Postman, page 41. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/297276/amusing-ourselves-to-death-by-neil-postman/

Haweya, On tailoring your social media experience. https://haweya.substack.com/p/on-tailoring-your-social-media-experience-8d5

Anne Carson’s oft-quoted translation of Euripides’ play Orestes, published in Carson’s book An Oresteia, page 218. To be clear: it is oft-quoted because it whips ass. You can buy it here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Oresteia-ANNE-CARSON/dp/086547916X

Intellectuals may know this one as the Fred Jones dilemma. https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/i-think-coolsville-sucks

David Foster Wallace, This is Water commencement speech. https://fs.blog/david-foster-wallace-this-is-water/

Fanny Howe, Doubt, republished in David Lehman’s “Great American Prose Poems: From Poe to the Present (2008),” pages 315-320. Thank you to Becca Human for making it available here: https://tinyurl.com/5aumm3vz

Nina Kang, The Lost Art of Memorizing Poetry, for “The American Reader.” https://theamericanreader.com/the-lost-art-of-memorizing-poetry/

Efim Etkind, The Translator, translated into English for “The Massachusetts Review” by Jane Bugaeva. Further reading about Gnedich are Douglas Murray’s article for “The Free Press” (link paywalled): https://www.thefp.com/p/douglas-murray-tatiana-gnedich and a bibliography from “Clever Geek”: https://clever-geek.imtqy.com/articles/1061705/index.html

George Steiner, History of Literacy lecture for “Living Literacies” 2002. 11:00-14:52. He speaks beautifully about Tatiana Gnedich while unfortunately getting almost every single fact about her wrong. Listen also from 21:21-27:12 if you enjoy him speaking and don’t mind joining the war on gatekeeping on the side of the gatekeeping.

absolutely wonderful read. cannot understate the hope it inspires in me - while reading this i thought back to those pieces of media that /have/ imprinted on me, that i hold in my mind, and realized i had more of them than i thought. this article makes me want to hold on to them so much stronger.

and i absolutely love that you touched on the meta web weaves - because there absolutely are tumblr or twitter posts that i think about, that have put into words feelings that i couldnt otherwise articulate. which is /all/ art, i suppose, longform or otherwise, but. its nice to see silly little twitter posts get that same attention in the article, because sometimes they do have value.

anyway im rambling. i wish you a good day, dear author!

Good morning! It’s Leigh. Hello!

It’s uncountable the number of times I’ve read this and been uncertain as to what to comment - because I do want to; this elicits a genuine reaction of both frustrated defensiveness and fervent agreement with so much of what you said. This quote in particular:

“When read properly, adoringly, deeply, one poem lasts a lifetime. You can stop buying.“

sends me to a shallow grave every time I read it. Because it does. It do. It sure fucking do. When I first read this, I was halfway through memorizing a poem that I - yes, I wanted to have it by my side, forever, if a solar flare cropped up and killed every piece of technology made in the last fifty years, I wanted it to be forever with me, to never have to rely on something outside my body to hold it for me. I was stuck, frozen, rereading this sentence over and over. That’s the first thing.

I gotta say though, as someone who absolutely has loved those sorts of posts on tumblr, it’s actually hard to like, not want to get mad in defense of ~web weaving~. I don’t know - I suppose I’ve thought of them more as the celebration of an idea shared between so many different people. You know that tweet, “the nature of humanity is just that every so often someone accidentally invents homestuck again”? (Now you do.) That’s what it makes me think of. That ten different people, artists, all shared the same thought, the same feeling, came to the same conclusion independently of one another - that we aren’t all so different, that we all feel this way about this thing, at least just a little bit.

But i suppose it’s a bit morbid, like you said - cherry-picking one creature out of an ecosystem and drawing a line to another, totally separate creature in a totally separate ecosystem without bothering with the evolution or the environment around them. I guess you just want it all to be easy sometimes, you know? That these conclusions can be drawn so simply. That you can pull from mountains and oceans and marshes and say look, these things are all the same. And you want it to be true so badly. But the eagle and the gull and the heron are still all birds, no?

It’s just that everything will always be out of context unless it is happening right Now. And you’re right, the superficial engagement with a tasting board of cherry-picked quotations spanning two hundred plus years is certainly one path to believing you’re engaging in art when in reality you’re barely snacking on passed hors d’oeuvres. But I don’t think that’s the only thing it is.

I’ve made one before - the nature of humanity, web weaving, whatever you want to call it. It was a painstaking process. It surrounded three pieces of music to which I wanted to give some context, provide food for thought, a new way of engaging with the art. I chose relevant quotes about the pieces themselves, pieces of art with themes that related to the music, moments of poetry that aligned with the form. And I like to think it worked, that people listened with an enriched ear, that they took what I offered and tried to connect the dots between the different media. But I know that it wasn’t Frankenstein’s monster, and I know it wasn’t reductive to the pieces of art themselves. They weren’t meant to represent themselves in whole, but to bolster a greater concept. The same thought, the same understanding, repeated over and over in different words and colors and patterns.

I told you yesterday I didn’t want to post the comment because I felt I was just restating your point again. I’ve given it thought (read: sleep) and I think I’ve kind of restated your point but in defense of web weaving? With most of the article devoted to the criticism of web weaving and then a hand motion at the end to say that in some circumstances it’s not so bad, and I’ve done the opposite: most of the comment in defense and then in the middle a hand motion to say that yeah, it’s got its pitfalls. I think I disagree with you on the ratio, or the percentage, or the amount of white and black the painter mixes into the gray.

Anyway, unless you really, really hate my opinion, let’s definitely be friends! It was nice talking to you yesterday and I wish I had more time. Byyyeeeee!!